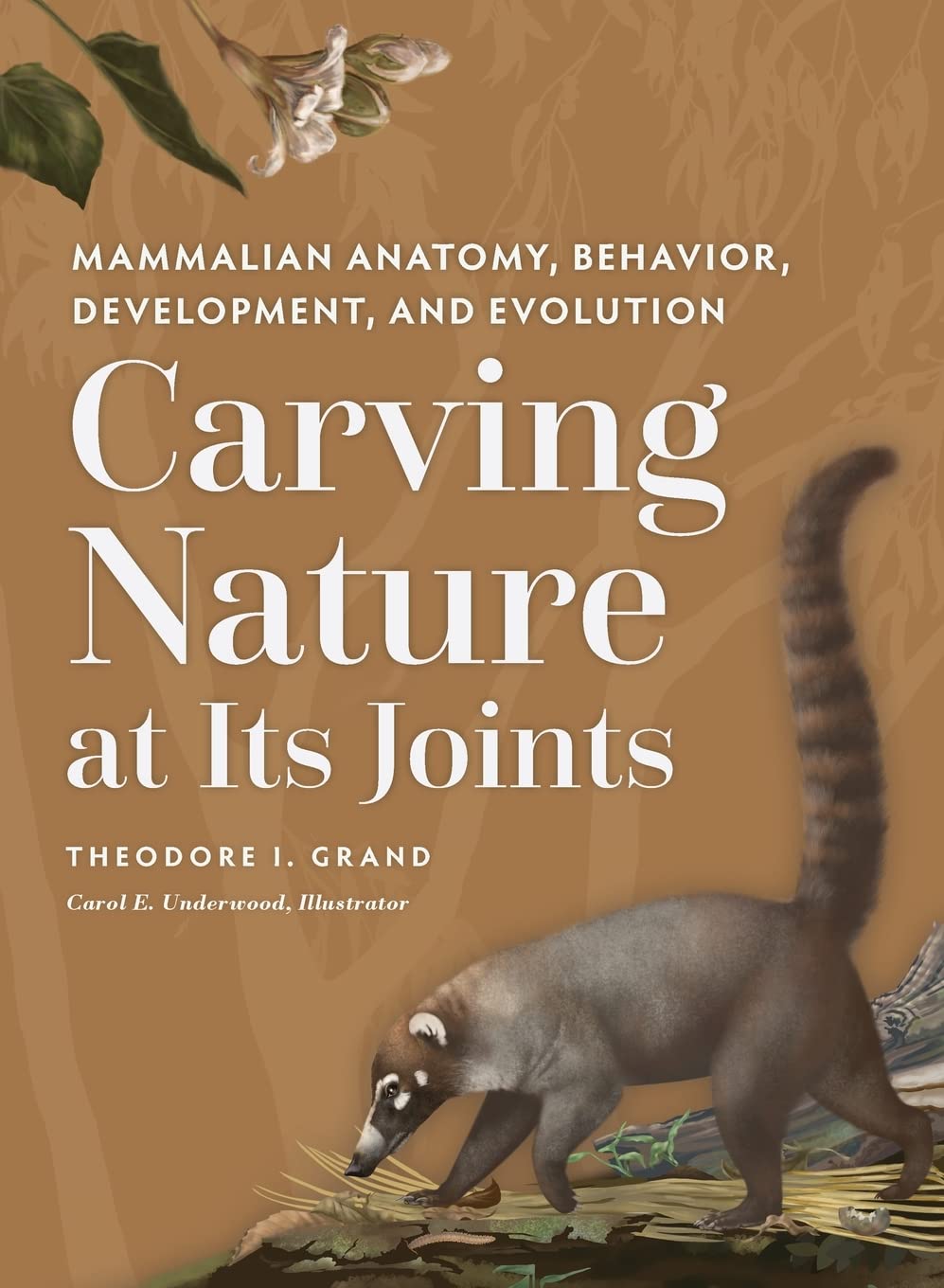

Carving Nature at Its Joints: Mammalian Anatomy, Behavior, Development, and Evolution

$30.60

| Brand | Theodore I Grand |

| Merchant | Amazon |

| Category | Books |

| Availability | In Stock |

| SKU | B0BFLCGVR5 |

| Age Group | ADULT |

| Condition | NEW |

| Gender | UNISEX |

About this item

Carving Nature at Its Joints: Mammalian Anatomy, Behavior, Development, and Evolution

Decoding the Body A Zen master and butcher by profession once said that until he understood the body he had repeatedly to sharpen his knives. After his illumination over the import of joint spaces, he never had to sharpen his implements again. Carving Nature at Its Joints surveys a variety of mammals from the mole to the rhinoceros. It offers fresh perspectives on anatomy, behavior, development, and evolution and explores Dr. Theodore Grand's methods for getting beyond-beneath, below, behind, and past-conventional top-down reductionist approaches. You will discover: why language is the primary wrinkle in the fabric of science; - why traditional disciplines are self-limiting; - why "parts and wholes" are less problematic for physical than for biological and social sciences; - why the buck stopped at Aristotle's laws of formal logic; - why we are wedged between opposed cognitive systems. No one writes about science like Ted Grand. An Eclectic by his own declaration, his iconoclastic, pluralistic, and scholarly argument emphasizes wholes over parts, the concrete over the abstract, the qualitative over the quantitative, and the complexity of life over the simplicity of the symbolic. In doing so, he takes organismal, comparative, and integrative biology to places where most Reductionists fear to tread. Grand's musings, grounded in the realm of the senses and buoyed by Carol Underwood's beautiful illustrations, teach us new ways to think about the complexities of mammals and the cognitive limits and traps of the humans studying them. Behavioral differences of individuals in the wild are linked to developmental changes in body composition. Behavior and development, in turn, become players in the historical analysis of evolution. Holism, history, and open-ended pluralism, Grand argues, are the approaches that let us escape reductionism's race to the explanatory bottom, as differing perspectives when taken together preserve the complexity that would otherwise be lost. Swimming against such a large cultural tide takes a rebellious attitude and a voracious expertise. With Grand, we get both. The result is a gift for anyone who's got a sneaking suspicion that something's fishy with the way that most of us are taught to do science. - John H. Long, Jr., Professor of Biology and Cognitive Science on the John Guy Vassar Chair of Natural History, Vassar College The Myth of Sisyphus After I had spent twenty years studying primates in Oregon, I wondered what species I would choose when I came to Washington. When my first paper on the kangaroos was complete and sent off, I saw the path my research would take. I had a flash of identification so strong that nothing in the past thirty years has changed it. Having tried to cheat Death, Sisyphus was condemned for eternity to a peculiar task—to push a huge rock up a mountainside only to have it roll back down the instant he reached the summit. Albert Camus attributed this futile, hopeless labor to an absurd world. I had reason to remember Sisyphus recently. I had pushed a research project uphill for several years; I had endured the thoughtful comments of colleagues and journal referees. I had become frustrated that I could not make clear to others what I had found, or worse, only thought I had found. Critical feedback at this stage in the process, the essence of science, tends always to be negative—what had not been understood, what could not be concluded. And even though I accepted this occupational hazard and kept going, I was becoming rocklike and dull. Positive comments, if they ever came, would be so far in the future as to be irrelevant. Nevertheless, as I returned the final revision to the journal's managing editor, I saw the product of my labor slipping away, rolling into the Valley of Public Knowledge, while I was already heading to the Valley of Ignorance and my next rock. Camus proposed that during Sisyphus's return to the base of the mountain he touched humanity, rising above the frustration of the ascent. Clearly, this is the case for scientists and artists. In the time before labor begins, one thinks, dreams, and hopes. Perhaps it will not be the biggest rock, likely not the most valuable, but it will be the one that holds personal interest, the one that teaches the self. Contained in that rock is the promise to renew one's existence. The trick is to select the largest rock you think you can handle, not the rock that interests someone else, and certainly not the heaviest rock someone pays you for. The gods condemned Sisyphus; as scientists, we volunteer ourselves. And whereas, beforehand, we can neither evaluate the task nor predict the difficulty of the ascent; and whereas, we cannot be paid enough for the frustration of our labor, we go on because of the promise of the descent. We exchange our labor for a window of hope. That is why Camus was probably correct: "One must imagine Sisyphus happy." DR. THEODORE GRAND received his undergraduate degree in bio

| Brand | Theodore I Grand |

| Merchant | Amazon |

| Category | Books |

| Availability | In Stock |

| SKU | B0BFLCGVR5 |

| Age Group | ADULT |

| Condition | NEW |

| Gender | UNISEX |

Similar Products

Compare with similar items

Liposculpture and Lipedema Surgery: A Gu... |

The Original Version of Christianity: A ... |

Mary Tudor: England's First Queen... |

Howling Legion (Skinners, Book 2): The S... |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | $29.99 | $20.00 | $14.02 | $6.39 |

| Brand | David M. Amron MD | Tamer Metwally | Anna Whitelock | Marcus Pelegrimas |

| Merchant | Amazon | Amazon | Amazon | Amazon |

| Availability | Unknown Availability | In Stock | In Stock | In Stock Scarce |